Mind the (Historical) Gap! English Pronunciation vs. Spelling

Nov 27, 2022

Follow our fictional character, Jane, through the ages, see how the language she speaks and writes changes, and find out why there’s such a big gap between spelling and pronunciation in English.

The year is 753…

...and Jane is tending the field. The English language she uses is similar to German. After all, it was the Germanic tribes that pushed the Celts toward Wales, Scotland, and Ireland upon arriving on the main island. Phonetically, they are also similar; words like father (English) and Vater (German) sound similar. They are quite different from some other languages spoken farther south, like French (père) or Spanish (padre). The vocabulary of her time has fewer words than contemporary English, but it is also more flexible. New words are easily created when needed by combining or modifying existing words such as beag ring, beaggyfa (ring-giver) lord, beaggyfu (ring-giving) generosity, and beaghord (ring-hoard) treasure. The grammar of the language she uses appears complicated to us. Its structure resembles modern German, where nouns have number, case, and gender (feminine, masculine, and neutral), the latter one corresponding to three different articles, nowadays substituted by "the". Although the Celts were the original inhabitants before the Germanic tribes arrived, Jane uses little of their language. The memory of them still resides in the names of the places, such as Kent, meaning “coastal district” or “land on the edge." Jane doesn’t understand Latin but has heard some of its words, such as scol (school, from Latin schola), when she visited a big town. She is illiterate, but if she could read, she would realize that it is very easy. The written and spoken English of the time are almost identical. They follow the rule “write as you speak."

The year is 976…

…and Jane (a descendant of the Jane from the previous passage) speaks different English. The Danes and Norwegians who plundered the lands and finally settled there brought many changes to the everyday language. Jane uses nouns such as bag and cake, and now-common verbs such as get and want, all coming from the newcomers. Even the pronouns didn’t stay the same; the Norse introduced them, their, and them. To be able to communicate more easily with the newcomers, the English dropped inflections at the end of the words. (Nowadays, the “s” used in possessive nouns like boy’s or plurals formed by adding an “s” (dogs) and the less common “en” (oxen) are the only remnants of those bygone days.) Jane can write and uses Latin letters combined with simple letters from runic writing. For example, she uses a special character called thorn and written like this: “þ”. This letter will be used until the beginning of the 16th century, when it will be replaced by “th”. Jane pronounces all the letters as she reads, so the “k” in knight and the “w” in write are not silent like they are today.

The year is 1288…

...and yet another Jane lives in a town where she cares for her big family. About two centuries before she was born, her lands were conquered by the Normans. They were originally Scandinavians who had settled in Normandy (Northern France) and attacked England from there. Jane uses some French words brought by the invaders, although their language is not pure French from that era but rather the Norman version. For example, Jane uses the word war, which comes from Norman werre and not French guerre. She now writes queen instead of cwen, another French influence. She often hears French from people of sophistication, noblemen, and scholars; while she says begin, they prefer to say commence. The French spelling is preserved, and this is the reason why, for example, city and center are pronounced with an “s." As a consequence, writing and reading become more separated.

The year is 1704…

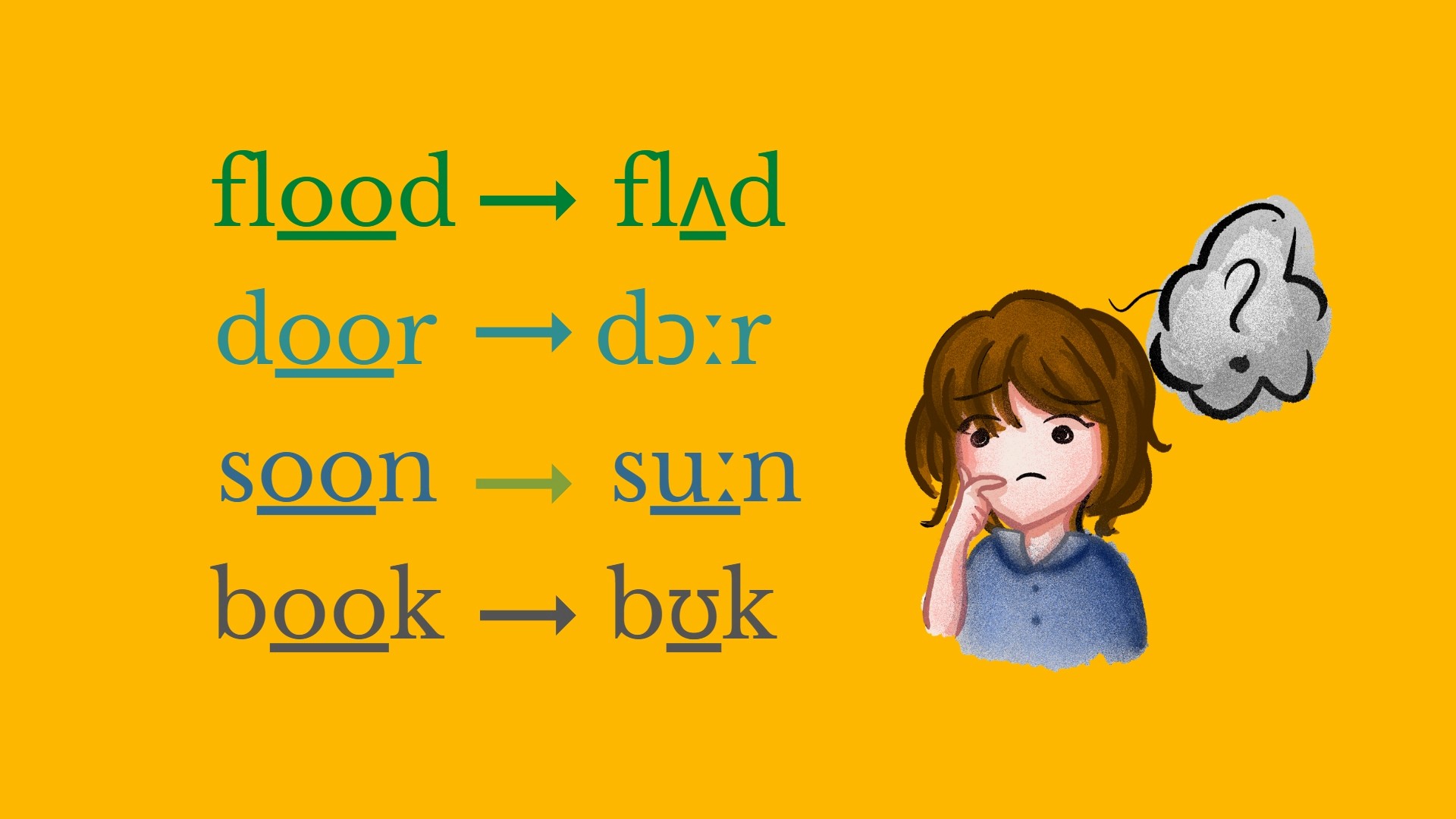

…and Jane has seen big changes around her. During the previous 200 years, Latin flourished since it was the language of Renaissance scholars. This led to the introduction of many new words into English. But now Jane is witnessing something else. English, rather than Latin, is becoming more commonly used, even at church, as the direct result of the Protestant Reformation. Yet the words that entered from Latin and Greek are preserved, and their original spelling is respected. Sometimes, the English spelling is even changed to bring it closer to the original, Latin, spelling. Such is the case with the word doubt (where a “b” is added to the Middle English word, doute, to make it closer to the Latin, dubitare). This also explains why philosophy and pharmacy are spelled with “ph” rather than “f”: they come from the Greek “phi” and not from Latin. Jane’s vocabulary has grown, an influence of the mixing of cultures in this epoch. She uses words from India, Turkey, and Italy, such as shampoo, yogurt, and violin. But one of the biggest changes from times past is how vowels are written and pronounced. Between the 15th and 17th centuries, the so-called Great Vowel Change occurred. Long “u:” became “ow” as in now, long “i:” became “ai” as in life, long “e:” became long “i:” as in been, and long “o:” became long “u:” as in food. These changes in pronunciation are not reflected in how the words are written, making the gap between these two even wider.

The year is 1875…

... and Jane, an avid reader, now uses a vocabulary that her namesake from the 18th century would have a problem understanding. Many new words are formed by merging two Latin or Greek words. Such is the word bioluminescence, which comes from bios (life in Greek) and lumen (light in Latin). Some other words that come from French changed the pronunciation and became more English-like, such as the word table. Another peculiar thing that happened was that some words that were originally English changed their spelling because of French influence. For instance, the word blue was originally spelled blew. Although the majority of vowels changed in the preceding period, there was one more shift that stands out. Until then, “ea” and “ee” were pronounced differently, but from this era on, their pronunciation is the same, as seen in the words bean and been. And considering that there haven’t been any significant developments in the 20th and 21st centuries, this is essentially where our tale stops.

As we have followed Jane through the ages, we have seen how English pronunciation and spelling have drifted farther and farther apart. As a result, it may not be surprising that efforts to align spelling with pronunciation have been made over the past 100 years. To this day, they have had no effect. The gap between how we write and speak English is likely here to stay, at least for the foreseeable future.

———

The five episodes from our story correspond to these four stages of the development of the English language:

Old English (450–1100)

Middle English (1100-1500)

Early Modern English (1500–1750)

Late Modern English (1750–1900)